* The answers to these West Side Story questions are all in the words of its creators: Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, Jerome Robbins and Stephen Sondheim. These distinguished gentlemen have discussed their reminiscences on the record for decades, which I have amassed from a variety of sources for today's special "Theatre Yesterday and Today."

Sixty-three years ago this evening, West Side Story, an innovate musical updating of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, set in what was then modern-day Manhattan, had its opening night at the Winter Garden Theatre. At the time, its principal creators were all well-established in their fields (except one). Arthur Laurents had already been represented on Broadway with four plays starring such heavyweights as Kim Stanley, Melvyn Douglas and Shirley Booth; the lead producer was Harold S. Prince, already a two-time Tony Award winner for The Pajama Game and Damn Yankees (that would accumulate to twenty-one, the record for any one person in the theatre); the music was composed by Leonard Bernstein who, for more than a decade, had been a superstar in both the classical world as well as the stage (On the Town, Wonderful Town and Candide). And the lyrics were by a twenty-seven-year old (twenty-five when first hired) named Stephen Sondheim. Yet even with all that, the most essential contributor was its director and choreographer, Jerome Robbins. It’s not for nothing there was also the additional “Conceived by” credit that Robbins insisted upon (much to Laurents’s dismay). The idea of a balletic update of Romeo and Juliet, set amidst warring gangs of 1950s Upper West Side, was one Robbins had mulled over for nearly ten years. What these artists came up with was historic. And today, on the occasion of its anniversary, I thought it would be fun to raise a few random questions, to which some may know the answers — and to which some may not. It all depends on how well you know your West Side Story.

First, just in terms of how the team worked together, some random quotes from the principals involved — including a funny story from the group's "novice.":

Jerome Robbins: "It was one of the most exciting I've ever had in the theater; the period of collaboration, when we were feeding each other all the time."

Leonard Bernstein: "This was one of the most extraordinary collaborations of my life, perhaps the most, in that very sense of our nourishing one another."

Arthur Laurents: "In my memory, it's the four of us together almost all the time. It's really true, without any self-consciousness of it we were all just high on the work and loving it."

Stephen Sondheim: "It certainly changed less from the first preview in Washington to the opening in New York than any other show I've ever done, with the exception of Sweeney Todd... on the way to the airport in Washington after a very nice run, I sad rather ingenuously to Jerry, 'Gee, this is my first show, and I wanted to have the experience of sitting up until three o'clock in the morning in a smoke-filled room rewriting the second act.' He looked at me in such anger and said, in effect, 'Take that back, don't ever say that out loud. Until you've been through it, you don't know what it's like.'"

Did Leonard Bernstein originally consider writing the score by himself?

The best answer to that question comes from Bernstein himself: “Yes, when we began I had — madly — undertaken to do the lyrics as well the music. In 1955, I was also working on another show, Candide; and then the West Side Story music turned out to be extraordinarily balletic — which I was very happy about — and turned out to be a tremendously greater amount of music than I expected, ballet, music, symphonic music, developmental music. For those two reasons, I realized that I couldn’t do all that music, plus the lyrics, and do them well.”

What was the nature of the Bernstein and Sondheim collaboration?

Almost exclusively, Sondheim set his lyrics to Bernstein’s musical ideas and motifs. According to Sondheim, in the specific case of “Gee, Officer Krupke” it was “the only song we wrote where the music in its entirety came first." It had actually been written as a vaudeville song in Bernstein’s previous show, Candide, when it was titled “Where Does it Get You in the End?” And it wasn’t put into West Side Story until Washington, D.C., three days prior to New York. Sondheim continues: “Jerry had been staging everything else, and we kept reminding him that this was a comedy number. And he kept saying, ‘I’ll get to it, I’ll get to it.’ One afternoon he did it in almost no time at all. Maybe the ideas had been cooking, but the staging of ‘Krupke’ is one of the most brilliantly inventive in one number I’ve ever seen … We had to yell at him to get it done, then he staged it in three hours by the clock.”

Why was “America” changed from the way it is performed on stage to the way it’s performed in the film version?

Stephen Sondheim writes in his 2010 book Finishing the Hat: “‘America’ was intended to be an argument between Bernardo and Anita, partly to enrich their relationship by adding some contention to it, since Arthur had no time in the libretto to explore it, but Jerry insisted that the song be for girls only, as it was his only chance for a full-out all-female dance number in the show. The character of Rosalia was invented to take Bernardo’s point of view. When the movie was made four years later, Jerry agreed to have the number danced by both the men and the women and to revert to the original lyric.”

Why did the numbers “Gee, Officer Krupke” and “Cool” switch places in the narrative from play to film?

On the West Side Story BluRay 50th Anniversary issue from 2011, Sondheim spoke on the commentary track: “‘Cool’ is the first song we wrote together … and I think Lenny had actually written, ‘Boy, boy, crazy boy. Stay cool, boy.’I think he had actually written that phrase, lyrically. I have a memory that it was already called ‘Cool,’ so I know he had done some work on it. And I think it was that opening line …

I had always felt that there was a displacement of numbers. I always thought that ‘Krupke’ should be in the first act when they’re still jazzing around and it’s that kind of thing — that they would be in the drugstore and sing — waiting for the Sharks to arrive for the war council. And that ‘Cool’ would be exactly that kind of number they would sing on the run from the police.

And Jerry said, ‘I see your point, but the problem is that I’ve designed (because he’d already staged ‘Cool’) for a full stage set.’ ‘Krupke’ is staged ‘in one,’ meaning the apron of the stage, the front of the stage. And he said, ‘I can’t change the set. But, if we ever do a movie …’ And we did a movie, and they switched the numbers around, and guess what? I was wrong. It works better the other way. Theatre truth is so different from truth-truth.”

When did the team know what they had: that the show would work?

It happened for all involved at the very first preview, best described by Bernstein: “It was an incredible night. It was August in Washington — horribly hot — and none of us knew whether anyone would listen to the show, or look at it, or stay in the theater. We’d had a lot of insults, a lot of warning: ‘You’re crazy,’ ‘Give it up,’ and so forth. At intermission I remember Justice Felix Frankfurter, the most distinguished man in Washington, in a wheelchair in tears. And this was only intermission. It was an incredible hello, because we didn’t know whether the show was even all right, let alone something special and deeply moving.”

As many are well aware, 2020 saw a brand new Broadway production of West Side Story, its run sadly suspended by the pandemic shut down. It had opened to generally excellent reviews and strong box office. The modern take on the show came from the mind of its inventive director, Ivo van Hove, the Tony Award winning Belgian theatre artist. And the year was supposed to close out with another master director, Steven Spielberg's new take on a film version (with a screenplay by Angels in America's Tony Kushner, no less). It was only announced two days ago that it will not be put out this year, but rather wait until movie cinemas are hopefully fully back in December of 2021, which is heartbreaking for all involved, I'm sure.

Lastly, for all that’s been said over the years about Jerome Robbins — how he had a cruel streak and tormented people — you can not take away his immeasurable contributions to the theatre. Personal feelings aside, Robbins own personal statement attests to the artistry of the man: “For me what was important about West Side Story was in our aspiration. I wanted to find out at that time how far we, as ‘long-haired artists,’ could go in bringing our crafts and talents to a musical. Why did we have to do it separately and elsewhere? Why did Lenny have to write an opera, Arthur a play, me a ballet? Why couldn’t we, in aspiration, try to bring our deepest talents together to the commercial theater in this work? That was the true gesture of the show.”

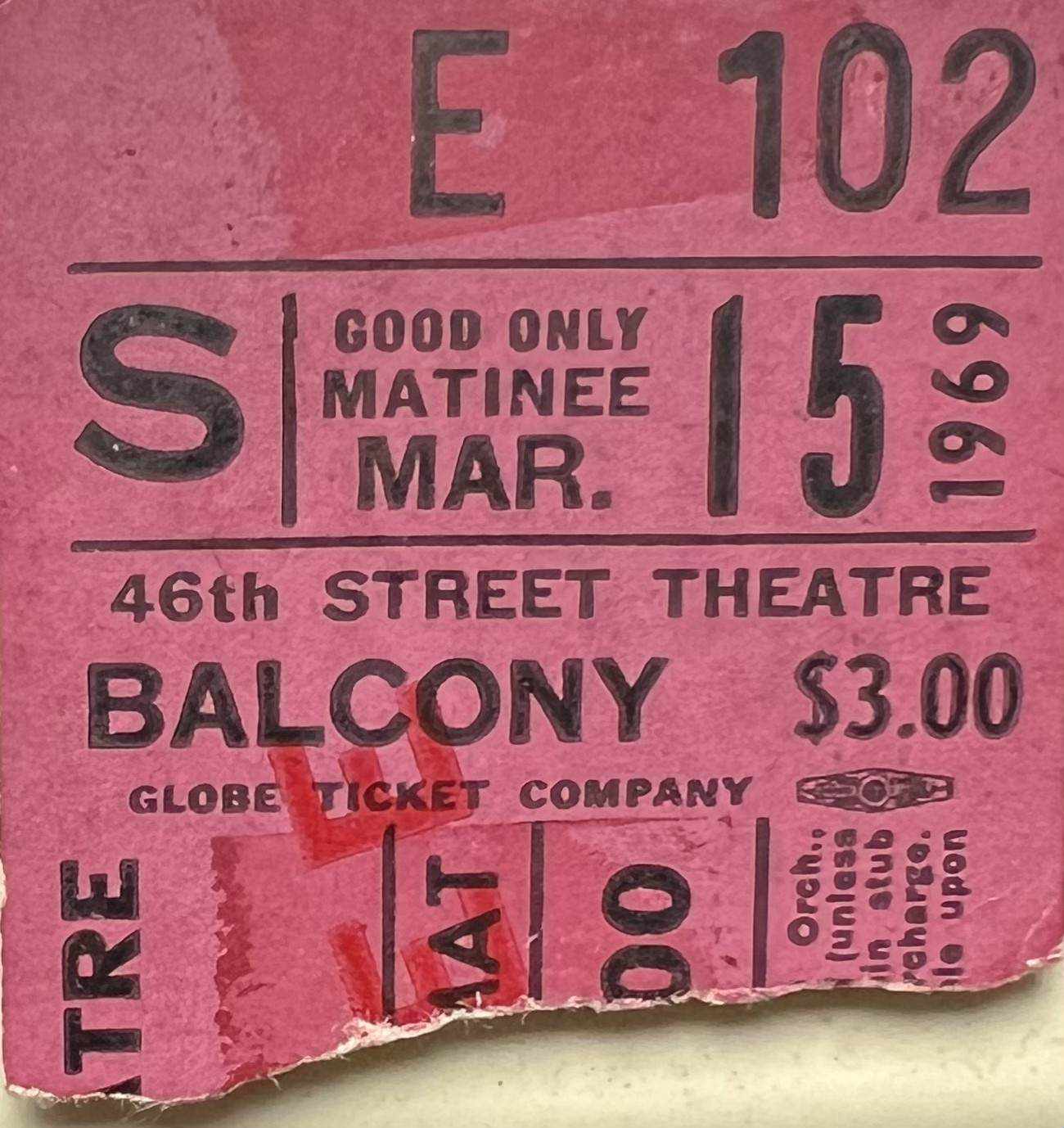

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...